The World of Montessori–November 14, 2022

When I walked into Bayside Montessori School I found myself surrounded by children scattered around the room on rolled-out mats completely immersed in their work. One child sat very focused at a table with Melissa Coy, the owner, teacher, and administrator, practicing his printing skills. The other children used a variety of concrete learning materials like number rods, sandpaper letters, and knobbed cylinders while they engaged in sensorial, mathematics, and language activities. I’ve been reading about Maria Montessori and the Montessori Method for several months now, and for my first visit to a Montessori classroom, my expectations were met, and even exceeded by what I observed and in discussion with Melissa and the head teacher, Jan. Our conversations and my tour of the classroom, in which Melissa highlighted the language and literacy-related materials and program, led me to a more comprehensive understanding of how literacy is taught and learned in a Montessori classroom. To back up a bit, I think it’s important to understand the origins of the Montessori Method, and know that while this early learning approach has been around for over a century, much of the foundational materials and activities remain the same. Maria Montessori was an Italian clinician who worked tirelessly in the field of family medicine, particularly with socially disadvantaged women and children. She established the first Casa dei Bambini or Children’s House in Rome in 1907 with the goal of providing children a favourable environment that allowed for freedom of movement and choice and personal responsibility. At that time in Italy and much around the world, children’s natural curiosity to explore the environment and self-select materials and activities was not a mainstream educational objective. Allowing the child to take the lead and responsibility in their learning was indeed a progressive idea, but an idea that quickly caught on in Italy, Europe, and across the globe. A holistic approach to learning that develops and educates the whole child, physically, intellectually, socially, and emotionally is a foundational philosophy of Montessori and likely what you would still see today across geographical and cultural contexts. So, what about literacy? I had some ideas going into Bayside Montessori about what I would see with respect to the literacy-related material, but it was indeed helpful to realize the work in action and hear directly from experts in the field. Similar to my experience at The Woods, literacy development is rooted in a language-rich environment. This is something that Maria Montessori certainly advocated for in her schools. Print was all around the room and accessible to the children, the teachers were engaged in several conversations with children individually and in small groups, and the materials that the children were using were associated with language, whether directly related to print or a language-related skill like vocabulary. As Melissa described, in any Montessori classroom the children begin building onto their language skills with games and lessons associated with phonological and phonemic awareness. “I Spy” is one particular lesson in which the children find an object that begins with the target sound. A teacher might say, for instance, “I spy, with my little eye, something that begins with /c/.” The child then finds an object in the room that begins with this sound. Pretty simple and straight forward, and a game that we all likely know and have played at some point in our lives. Yet, this type of game provides children with opportunities to play with the sounds of English. Isolating and manipulating individual sounds in spoken words, known as phonemic awareness, sets a foundation for spelling and word recognition skills. Interestingly, in a Montessori program children begin encoding or writing words before reading (although the two certainly go hand-in-hand). Once a child has begun to associate phonemes with the corresponding letter or combination of letters, they start putting the letters together to create and write words. The teachers consistently refer to the letter symbols by the sounds they make, so the children learn the sounds before they learn the letter names, which makes sense given that the goal of this initial stage of word-level reading is to blend and segment the sounds in written words (not the letter names).

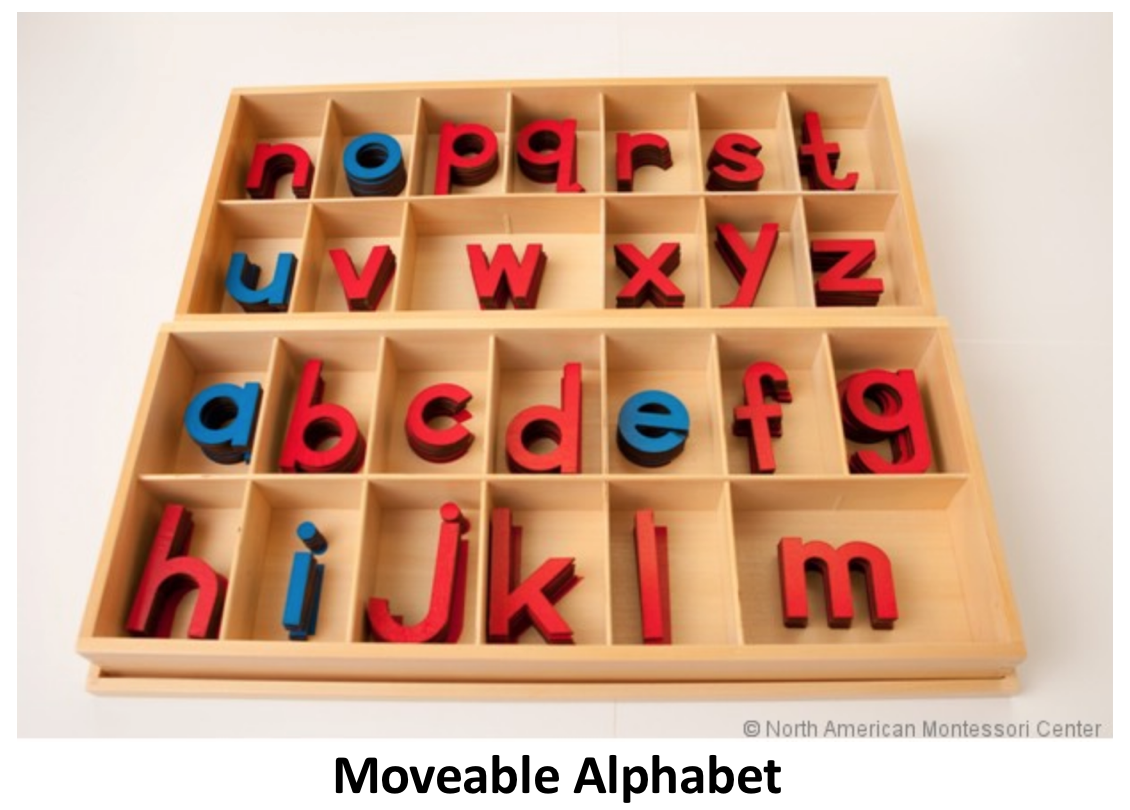

Learning the letter sounds and beginning to blend sounds together to make words is a systematic and explicit process, as it is in many early years and primary programs. In a Montessori classroom, the process is also multisensory which benefits all children. Reading and writing are visual, auditory, and tactile activities. Take the Sandpaper Letters activity, for instance. As children say the sound of the letter they feel the shape of the letter by tracing them in sand with their fingers. The Moveable Alphabet also allows the children in a Montessori classroom to touch, feel, and work with wooden letters to make words. The tactile and multisensory experience can be engaging and a focus for children’s attention (for a short read on the value of a multisensory approach check out this article: Phonics Instruction: The Value of a Multisensory Approach). The order in which the letter sounds are introduced is systematic, where a set of letter sounds, like /s/, /m/, /a/, and /t/, are taught together. This allows the child to begin to make and read words right away, which is indeed a tremendous feat and motivating too! Scope and sequences for introducing letter sounds are becoming more and more accessible to teachers across contexts, all with the same goal of learning the letter-sound correspondences and beginning to encode and decode words. At Bayside Montessori School, as a child works through the sets of letter sounds they also begin to read from decodable or phonetic books. These print-based activities are done in conjunction with language-related activities, like building vocabulary and oral language skills with read alouds, storytelling, and speaking during circle time (or any time of the day!). All of these experiences certainly coincide with The Simple View of Reading, where reading comprehension is a product of both decoding and language-related skills. It’s been interesting to me to learn that the Montessori Method has taken a phonetic approach to teaching reading since it’s conception over a century ago. In a program with such a consistent curriculum and one that aligns with the science of reading, the Montessori approach hasn’t been influenced by current trends or packaged (and pricey) programs, like we sometimes see in other contexts. I am incredibly grateful to Melissa for allowing me to venture into the world of Montessori. I will be visiting Italy in the spring, and as part of my travels I plan on touring around Rome and seeing Montessori’s first Casa dei Bambini (see The Children's House, my post about this visit). I also hope to talk to Montessori teachers in Rome and elsewhere about their perspectives of literacy. I imagine I’ll hear recurring ideas and see patterns across these contexts. At the same time I wonder about the role language plays on teachers’ perspectives and whether language differences impact how teachers across countries view reading development and instruction. -Pamela

The World of Montessori–November 14, 2022