“Snake is Slowly Slithering, Over the Soft, Soft Ground…”–November 28, 2022

When I taught kindergarten I would often take pieces of programs rather than use one entire program on its own for my language and literacy instruction. Jolly Phonics was one of the programs that I used for teaching the letter-sound relationships, partly because it was available in the school I was teaching in, but also because it took a systematic and explicit approach. Sets of five or six letter sounds are introduced at a time so that children can begin decoding and encoding words right away, before they’ve mastered all the 44 letter sounds of English and the letters or combination of letters that represent them. The first set, for instance, is /s/, /a/, /t/, /p/, /i/, and /n/. You can probably think of quite a few words that use a combination of these letters and letter sounds (sit, tip, pin, it, in, pants, paint...).

The sets of letter sounds that were introduced to the children, the big books and songs that accompanied each letter sound, and the program’s multisensory approach are all components of Jolly Phonics that I enjoyed, and that the children enjoyed too (from the photo above, it's clear that my son Eli enjoys the program as well).

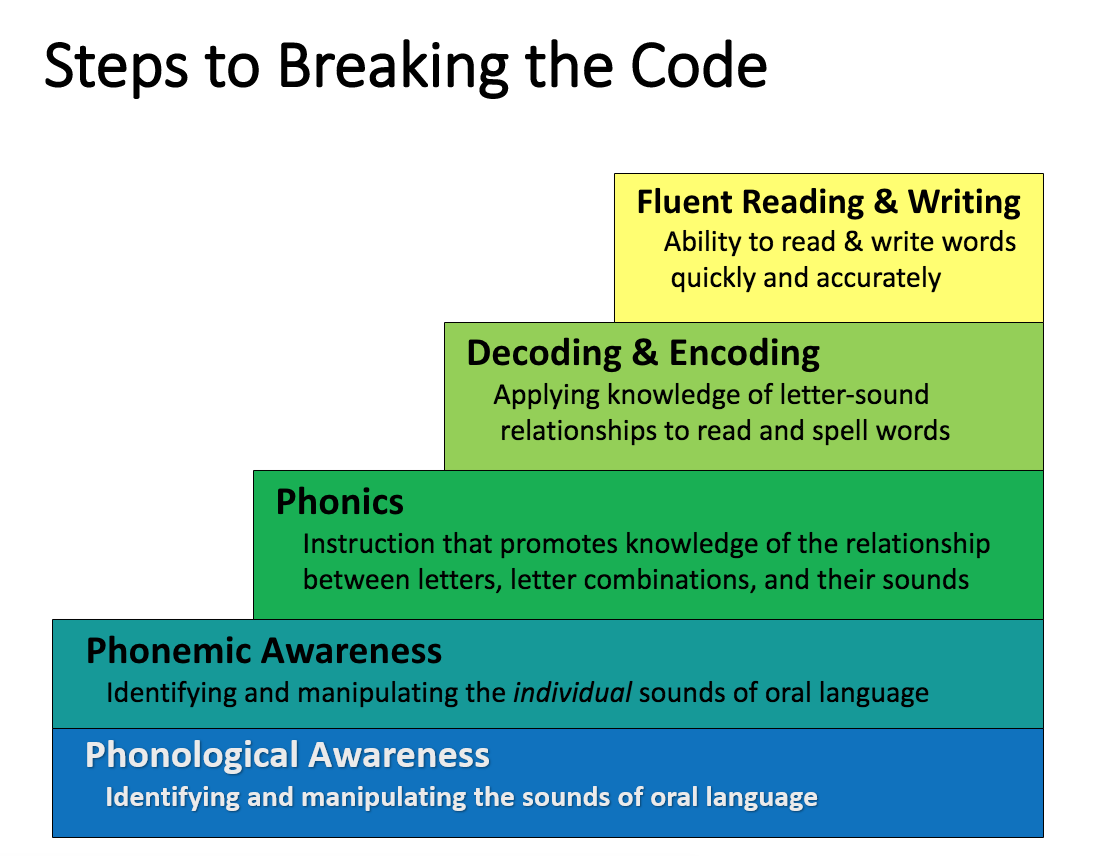

Phonics instruction (for alphabetic languages, like English) has been around for decades, centuries really. Teaching the letter-sound relationships for reading and spelling in a systematic and explicit way is a necessary component of any beginning reading program, the research on this is clear. Yet at times, phonics instruction has been a contentious topic with some schools and school districts asking their teachers to remove their phonics charts from the walls and stop using their decodable or phonetic books with their students. Of course, phonics does not make up an entire reading program, and it does not just mean drills and memorization. Kindergarten and primary grade teachers certainly know phonics games and activities that are motivating and engaging, and still take a systematic and explicit approach. Phonics and decoding skills are just one area of reading (citing the Simple View of Reading again...), and the amount of time that a teacher should spend on phonics and decoding skills depends on a child’s stage of reading development. Jeanne Chall wrote about the stages of reading and how the proportion of time spent on reading components changes as children move from one stage to the next. Dale Willows has also written about the stages of literacy development and provides nice visuals to show the proportion of skills that should be emphasized at each stage. Those at stage 3, for instance, have built strong foundational reading skills so that they read to learn new ideas, gain new knowledge, and learn about new perspectives. I also like thinking about decoding as just one of the steps, albeit an important step, to breaking the code and becoming a fluent reader. Having phonological and phonemic awareness as well as a strong understanding of letters, letter combinations, and their sounds contributes to a reader’s ability to apply their knowledge of letter-sound relationships to read and spell unfamiliar words, and ultimately, to be able to automatically recognize words and read with fluency and accuracy. Fluent readers can then spend more cognitive resources on actually comprehending and thinking more critically about what they are reading.

The sets of letter sounds that were introduced to the children, the big books and songs that accompanied each letter sound, and the program’s multisensory approach are all components of Jolly Phonics that I enjoyed, and that the children enjoyed too (from the photo above, it's clear that my son Eli enjoys the program as well).

Phonics instruction (for alphabetic languages, like English) has been around for decades, centuries really. Teaching the letter-sound relationships for reading and spelling in a systematic and explicit way is a necessary component of any beginning reading program, the research on this is clear. Yet at times, phonics instruction has been a contentious topic with some schools and school districts asking their teachers to remove their phonics charts from the walls and stop using their decodable or phonetic books with their students. Of course, phonics does not make up an entire reading program, and it does not just mean drills and memorization. Kindergarten and primary grade teachers certainly know phonics games and activities that are motivating and engaging, and still take a systematic and explicit approach. Phonics and decoding skills are just one area of reading (citing the Simple View of Reading again...), and the amount of time that a teacher should spend on phonics and decoding skills depends on a child’s stage of reading development. Jeanne Chall wrote about the stages of reading and how the proportion of time spent on reading components changes as children move from one stage to the next. Dale Willows has also written about the stages of literacy development and provides nice visuals to show the proportion of skills that should be emphasized at each stage. Those at stage 3, for instance, have built strong foundational reading skills so that they read to learn new ideas, gain new knowledge, and learn about new perspectives. I also like thinking about decoding as just one of the steps, albeit an important step, to breaking the code and becoming a fluent reader. Having phonological and phonemic awareness as well as a strong understanding of letters, letter combinations, and their sounds contributes to a reader’s ability to apply their knowledge of letter-sound relationships to read and spell unfamiliar words, and ultimately, to be able to automatically recognize words and read with fluency and accuracy. Fluent readers can then spend more cognitive resources on actually comprehending and thinking more critically about what they are reading.

As much as there should be an emphasis on phonics instruction in the early grades or stages of reading, this emphasis shouldn’t neglect language-related skills, like critical thinking while reading and developing critical literacy, vocabulary, and background knowledge. The report from the National Reading Panel showed that daily phonics instruction shouldn’t be more than 30 minutes. The rest of the language curriculum and how language is embedded across subjects should provide ample opportunities to not only practice word-level reading skills but also to support the development of language-related skills. This balance between print and language-related skills, like vocabulary, background knowledge, and reading comprehension has certainly been the case during my school visits so far, at Origins Academy in New Brunswick, and more recently at Bayside Montessori. Teachers across these two very different schools are fostering decoding and word-recognition skills using explicit and systematic instruction as well as building language-related components through direct instruction as well as outdoor learning, play, storytelling, and purposeful classroom discourse.

This type of balance between teaching and developing print-related and language-related skills is something that teachers have been doing across different educational eras (whether their school districts support it or not). And this continues to be the case. The conversations I’ve had with teachers lately indicate their dedication and how reflective they are in their literacy planning and instruction. The teachers I’ve been talking to understand the importance of being explicit and using structured literacy so that skills are taught in a systematic way. These same teachers consider how language and literacy can be fostered across subject areas and in language-rich environments, and how a research-based program incorporates several components of literacy (phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, morphology fluency, reading comprehension, critical literacy, oral language...), not just phonics or reading comprehension strategies. As I write this I’m reminded of the amazing work teachers do and their dedication to being life-long learners. Louisa Moats sums it up nicely: “Teaching reading is rocket science...But it is also established science, with clear, specific, practical instructional strategies that all teachers should be taught and supported in using.”

-Pamela

As much as there should be an emphasis on phonics instruction in the early grades or stages of reading, this emphasis shouldn’t neglect language-related skills, like critical thinking while reading and developing critical literacy, vocabulary, and background knowledge. The report from the National Reading Panel showed that daily phonics instruction shouldn’t be more than 30 minutes. The rest of the language curriculum and how language is embedded across subjects should provide ample opportunities to not only practice word-level reading skills but also to support the development of language-related skills. This balance between print and language-related skills, like vocabulary, background knowledge, and reading comprehension has certainly been the case during my school visits so far, at Origins Academy in New Brunswick, and more recently at Bayside Montessori. Teachers across these two very different schools are fostering decoding and word-recognition skills using explicit and systematic instruction as well as building language-related components through direct instruction as well as outdoor learning, play, storytelling, and purposeful classroom discourse.

This type of balance between teaching and developing print-related and language-related skills is something that teachers have been doing across different educational eras (whether their school districts support it or not). And this continues to be the case. The conversations I’ve had with teachers lately indicate their dedication and how reflective they are in their literacy planning and instruction. The teachers I’ve been talking to understand the importance of being explicit and using structured literacy so that skills are taught in a systematic way. These same teachers consider how language and literacy can be fostered across subject areas and in language-rich environments, and how a research-based program incorporates several components of literacy (phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, morphology fluency, reading comprehension, critical literacy, oral language...), not just phonics or reading comprehension strategies. As I write this I’m reminded of the amazing work teachers do and their dedication to being life-long learners. Louisa Moats sums it up nicely: “Teaching reading is rocket science...But it is also established science, with clear, specific, practical instructional strategies that all teachers should be taught and supported in using.”

-Pamela

Snake is Slowly Slithering…-November 28, 2022